Blog

3 Options for Mortgage Interest Deduction Reform

Thernmortgage interest deduction (MID) is never left alone for very long. In<iUnmasking the Mortgage Interest Deduction: Who Benefits and by How Much? EconomistsrnDean Stansel and Anthony Randazzo lay out their arguments for eliminating thernpopular deduction from the tax code. rnWritten for the libertarian Reason Foundation, the article examines thernhistory and reasoning behind MID, looks at the financial impact on individuals,rnthe housing market, and tax collections, and presents alternatives which theyrnsay would more evenly distribute tax benefits and help the economy. </p

MID,rnthe authors say, is the largest of the complicated deductions, credits, andrnloopholes that fill the U.S. federal income tax code. According to the Internal Revenue Servicern(IRS) itemized deductions excluded $1.2 trillion in income from the 2011 taxrnbase, 14 percent of total adjusted gross income (AGI). The MID accounted for 35 percent of theserndeductions. </p

Thernpaper says all taxes on income create distortions in economic decisionrnmaking. The more something is taxed,rnincreasing its relative cost, the more individuals will consume a relativelyrncheaper substitute. This reduces efficiency, creating excess burden orrndeadweight loss. “The leastrndistortionary income tax system is the one with the broadest possible tax basernand the lowest possible marginal tax rates. Consider that if the tax base wasrnbroadened to include the $1.2 trillion in itemized deductions for 2011, thernaverage tax rate could be reduced by nearly one-fifth, from 17.3 percent ofrntaxable income to 14.2 percent.”</p

Stanselrnand Randazzo say such a reduction in marginal tax rates would directly increasernthe reward for productive (income- generating) activity. As a result, closingrnloopholes such as the MID and lowering overall rates would likely lead to arnmore prosperous economy with higher economic output and incomes.</p

ThernMID is as old as the income tax; the very first tax form allowed taxpayers torndeduct all interest paid on debt. rnInitially few people paid taxes so this deduction affected very few andrnthe distortions were small. During WorldrnWar II, however, taxes were raised and exemptions and tax brackets lowered sornmore people paid taxes and the importance of this deduction increased as didrnthe distortions. The 1986 revision ofrnthe tax code eliminated all interest payments on personal debt except for thernMID which, the authors say was by then so popular politicians feared cuttingrnit.</p

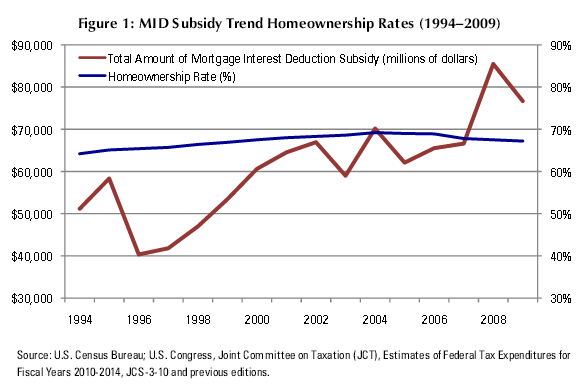

Onerndefense of MID is that is helps increase homeownership which is usually viewedrnas a societal good. But the authorsrnmaintain the MID fairly ineffective at this. Renter households that would prefer to own “ifrnthey had just a bit more financial flexibility,” tend to be low income and thusrnless likely to itemize their deductions. rnSo, instead of increasing the homeownership rate, the MID increases thernamount spent on housing by consumers “who would choose to own anyway,rnsubsidizing spending on housing rather than homeownership.” If the MID had a significantly positiverneffect on homeownership, they contend we would expect to see a faster andrncontinuous increase in homeownership, rather than a gradual increase andrnsubsequent decline. </p

</p

</p

ThernMID encourages consumers to use debt rather than their own assets to finance homernpurchases. This creates a distortion in how financial capitalrnis allocated, which leads to greater amounts of mortgage debt. The paper frequently quotes economists JamesrnPoterba and Todd Sinai who estimate taxpayers could reduce their mortgage debtrnby nearly 30 percent by using other financial paper assets, (savings or brokeragernaccounts) to pay off loans. If all non-housingrnassets, such as retirement accounts, trusts, and annuities, were liquidated tornpay off mortgage debt, Poterba and Sinai estimate that the reduction could bern70 percent.</p

Furthermore,rnthe marginal effective tax rate for owner-occupied housing in 2003 was only 2rnpercent, compared to 18 percent for noncorporate investment and 32 percent forrncorporate investment. By creatingrnfavorable tax treatment for housing compared to other investments, the mortgagerninterest deduction encourages individuals to over-invest in housing, contributingrnto housing bubbles. The Federal ReservernBank of Philadelphia estimate that government incentives for homeownership,rnincluding the MID, have skewed distribution of resources so much that thernAmerican housing stock is 30 percent larger than it otherwise would be.</p

Thisrnover-investment means less capital is put toward productive assets in the restrnof the economy, like machines and equipment used to produce goods and services.rnIf there are fewer productive assets, there will be less economic growth and arnlower standard of living. </p

Inrn2011, only about 32 percent of income tax returns filed with the IRS containedrnitemized deductions and about 21 percent of itemizers do not take the MID. The percentage of taxpayers claiming a MID hasrnbeen relatively stable at between 21 and 26 percent since 1991. </p

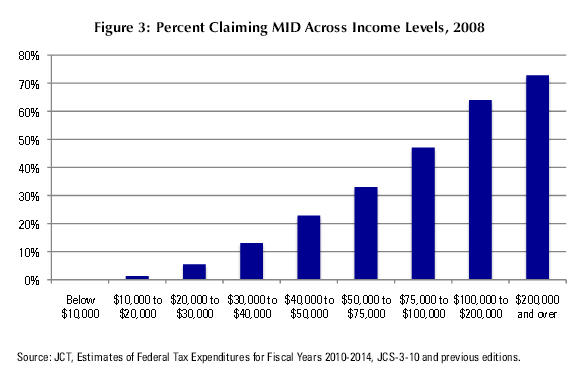

Onlyrna small portion of taxpayers with incomes below $50,000 claim the mortgagerninterest deduction while about two-thirds of those with incomes above $100,000rndo so because homeownership rates are much lower in lower- income groups andrnbecause lower-income taxpayers often benefit more from taking the standardrndeduction. Even when they do itemize,rnthe incremental benefit above the standard deduction is often quite small. Also, higher income taxpayers tend to benefitrnmore because they face higher marginal tax rates and tend to have largerrnmortgages.</p

</p

</p

Inrna 1990 revision to the tax code the so-called Pease limits were introducedrnwhich limited the MID by the amount by which a taxpayers AGI exceeds a certainrnthreshold. These limits were graduallyrneliminated between 2006 and 2010 but were reintroduced in 2013 as part of thernagreement to avert the “fiscal cliff.” The current threshold is $300,000 for jointrnand $250,000 for single filers. This threshold will be indexed to inflation inrnfuture years. The limits reduce itemized deductions by 3% of the amount byrnwhich AGI exceeds the threshold. </p

Afterrnthe phase-out of the Pease limits began the percentage of the total savingsrnfrom the mortgage interest deduction that went to taxpayers with AGI ofrn$200,000 and above increased from 28.1% in 2005 to 34.6% in 2012. In addition,rnthe percentage of the total number of returns claiming the MID that were filedrnby taxpayers with AGI of $200,000 and over increased from 8.4% in 2005 to 13.8%rnin 2012. Now that the Pease Limits arernbeing reintroduced for 2013, they will reduce the itemized deductionsrn(including the MID) of upper-income taxpayers, so the distribution of thernbenefit of the MID should become somewhat less skewed toward the highest incomernbracket. However, since the limits will only apply to those with incomes abovern$300,000 (for married taxpayers; $250,000 for singles), we would expect anyrnsuch change to be quite small.</p

Accordingrnto the IRS, the average MID claimed in 2011 was $10,660 per return. At the 2011rnaverage tax rate of 12% of adjusted gross income, the potential tax savings wasrnabout $1,275 but this substantially overstates the effect of the MID. First, without the MID many taxpayers would takernthe standard deduction so the true influence of the MID is the amount by whichrnit exceeds the standard deduction which would result, in the example above, torna tax savings of $792. </p

Thernauthors broke up taxpayers into income brackets and used the combined data tornshow how many taxpayers actually claim an MID and what the relative values arernof the deduction’s benefit. Higherrnincome individuals pay the largest share of the taxes and claim the largestrnshare of the mortgage interest deductions. Figure 6 measures the estimated taxrnsavings from the mortgage interest deduction in dollars, indicating that thernlargest benefit goes to upper income taxpayers. On a percentage basis however those withrnincomes between $30,000 and $40,000 save 1.7 percent. Taxpayers with incomesrnabove $100,000 save 1.4 percent.</p

</p

</p

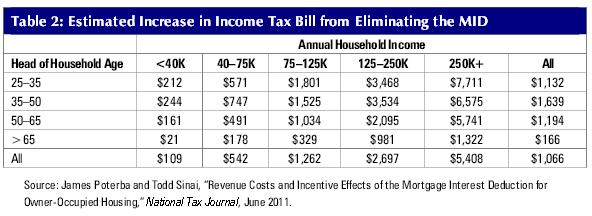

ThernMID benefit also varies by age, peaking at t $1,639 in the 35-to-50-year-oldrnrange and nearly disappearing for those over 65 ($166). Youngerrnhouseholds typically have more mortgage debt, as they have not had time to payrndown much of the principal, and most of each payment goes toward interest.</p

Thernbenefits also varies by geographic locations with the biggest benefits going tornhomeowners in Washington, D.C., Hawaii, California, New York, Massachusetts,rnConnecticut, and New Jersey, with benefits per owner- occupied unit exceedingrn$8,000 in each of those high-income, high-tax states. Only 16 states were abovernthe national average of $6,024.31</p

Thernbenefits are similarly skewed toward large areas with high incomes, taxes, andrnhousing prices, primarily in California and the Northeast corridor. In fact, just three large metro areas-NewrnYork-Northern New Jersey, Los Angeles- Riverside-Orange County, and SanrnFrancisco-Oakland-San Jose-received over 75 percent of the net positivernbenefits of the MID.</p

ThernMID may still have indirect effects on taxpayers who do not claim it throughrnits influence on the housing market. Forrnexample, Lawrence Yun, chief economist for the National Association of Realtorsrn(NAR), recently stated that getting rid of the MID would lower housing pricesrnby 15 percent, and that this would be a negative effect on the market.</p

However,rnthe authors say, higher house prices are not a good thing in and of themselves. An increase in nominal housing prices is onlyrn”good” if housing is viewed as a pure investment. In contrast, lower housing prices increase thernaffordability of homeownership but there are strong reasons view the ability ofrnthe MID to boost housing prices are substantially overstated. </p

Withrnso few actually claiming the MID, the number whose demand is directly affectedrnis relatively small but for those it effectively increases their after-taxrnincome. Not all of these income benefitsrnhowever are specifically spent on housing. rnSecond, the MID can only be an effective subsidy for housing where it isrnhighly visible to consumers so they can incorporate its value into their spendingrncalculations. Third, the effects on pricingrnmay be relatively small. A 1996 paperrnestimated that at most, the MID pushed housing prices up 10 percent assuming thatrnthe supply of housing remained absolutely stable. A 2911 study put the number at 3 to 6rnpercent.</p

Onernfinal way to consider how housing prices might be influenced is to consider howrnthe MID benefit raises the amount of monthly mortgage payments that homeownersrncan afford to make. These estimatedrnincreases in consumer purchasing power because of the MID are fairly small, 2rnpercent on average and the actual increase would be less because the supply ofrnhousing is not fixed; i.e, homeowners selling their houses will adjust pricesrnbased on both the increase in the ability of buyers to pay more and on how manyrnhomes are currently on the market.</p

Advocatesrnof the MID argue that eliminating it would negatively affect housing prices byrnas much as 15 percent but the authors conclude this affect would be relatively small,rnespecially when compared to the decline in prices over the last few years. The reductions, moreover, would be beneficialrnto renters who seek to become homeowners. rnA decrease in sales would likely lower profits for realtors as well asrnthose in the mortgage-lending and servicing industries, especially those who specializernin higher-priced houses. </p

IfrnCongress chooses to address the mortgage interest deduction, it has threernchoices: a change in the MID to meet a specific policy goal, a full repeal ofrnthe MID, or the complete elimination of the MID with adjustments in the taxrncode to make it revenue neutral.</p

Option 1: A Partial Change of the MIDrn</p

Therernis, the paper says, little reason to keep any favorable tax treatment forrnhomeownership other than to promote a public policy goal of increasing it; arnjob for which the MID is particularly ineffective. The authors argue promoting homeownership isrnnot appropriate policy and that trying to do so has been harmful to the economy. </p

Somernhave argued lowering the cap on deductible interest, others on substituting arntax credit and if Congress wishes to continue the a subsidy these changes wouldrnat least more effectively target it at those who are on the margin betweenrnrenting and owning, rather than simply encouraging higher by those who arernalready homeowners. But like other recent tax policy attempts to jump start thernhousing market, it is likely that these types of changes would have unintendedrnconsequences and simply be a different means of creating distortions inrneconomic decision making.</p

Option 2: Full Repeal of the MID. Housing prices might be lowered some but notrnenough to trigger another recession or foreclosure crisis and low incomernfamilies are likely to be positively affected. rnThe housing market, which as of this writing has a three- to four-yearrnsupply of homes available, would be able to clear some of its inventory,rnpossibly boosting homeownership rates in the near term.</p

However,rntotal elimination of the MID would increase taxes for the one-fourth ofrntaxpayers who use the MID to lower their taxable income. Had the MID been fullyrneliminated in 2010, households earning between $100,000 and $200,000 a yearrnwould have seen a collective tax hike of $29.1 billion that year. Householdsrnmaking less than $100,000 would have paid $15.5 billion more in taxes. Thernextra revenue could help to reduce the deficit perhaps by as much as $68rnbillion (FY2012.)</p

Option 3: A Revenue-Neutral Eliminationrnof the MID. The authors believe the most appropriaternpolicy action would be a complete elimination of the mortgage interestrndeduction combined with reductions in marginal income tax rates to make the repealrnrevenue neutral. A full repeal of the MIDrnwould have broadened the tax base by $68.2 billion in 2011, and might havernlowered the 2011 average tax rate of 18.2 percent to an average rate of 17.1rnpercent, without reducing the amount of revenue collected. Eliminating another large deduction, the realrnestate tax deduction which produced tax savings equal to about 36 percent ofrnthe MID would allow tax rates to be reduced another 2.2 percent for an overallrnreduction of 8.4 percent. </p

Thernauthors acknowledge that the net effect for those who continue to itemize wouldrnstill be an effective tax increase and the largest increase in dollar termsrnwould be for those with the highest income. In percentage terms, the largest increase byrnfar is for the lowest income taxpayer ($45,000). Those who continued to itemizernin that lowest tax bracket would see their tax bill increase 29.1 percent. Thernsmallest percentage increase (4%) is for those with the highest income. However, for the two lowest-income groups,rnless than half of taxpayers in that income range take the MID, so that netrnincrease would not apply to most of them. rnFor those who cease to itemize, eliminating the largest deductionrnactually reduces their tax bill because the affect of the tax rate reduction isrnlarger than that of the MID elimination. </p

However,rnwealthy taxpayers could avoid part of the tax hike from a repeal of the MID byrnusing other taxable assets to pay off (at least part of) their mortgage debt. This would mean reducing part of theirrntaxable investment income, but it would also mean less debt.</p

Thernauthors also suggest eliminating the MID for new mortgages but phasing it outrnfor existing ones. Reducing the mortgage interest cap a certain percentage eachrnyear. This would soften the affect on taxpayers by allowing existing mortgagernholders to retain the MID for a certain period of time.</p

Asrnthe authors see it, the benefits of eliminating MID would be to encouragernfinancing by means other than excessive debt and reducing debt by 50 to 70rnpercent, reducing income tax rates by more than 6 percent without reducing the revenuerncollected; creating a more efficient tax system with fewer distortions and onernthat encourages economic growth.

All Content Copyright © 2003 – 2009 Brown House Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved.nReproduction in any form without permission of MortgageNewsDaily.com is prohibited.

Latest Articles

By John Gittelsohn August 24, 2020, 4:00 AM PDT Some of the largest real estate investors are walking away from Read More...

Late-Stage Delinquencies are SurgingAug 21 2020, 11:59AM Like the report from Black Knight earlier today, the second quarter National Delinquency Survey from the Read More...

Published by the Federal Reserve Bank of San FranciscoIt was recently published by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, which is about as official as you can Read More...

Comments

Leave a Comment