Blog

Fed Paper asks if we are "Mortgaging the Future?"

Three economists writing for thernFederal Reserve Bank of San Francisco’s EconomicrnLetter, are theorizing that the explosion of lending, especially mortgagernlending, has played a more important role in shaping the business cycle thatrnpreviously thought. If they are correct,rnthey say, then economic policy must adapt to this reality.</p

In their paper, “Mortgaging the Future?”rnthe three, Oscar Jordà vice president in the Economic ResearchrnDepartment of the Bank, Moritz Schularick, professor of economics at thernUniversity of Bonn; and Alan M. Taylor professor of economics and finance atrnthe University of California, Davis say that bank lending has quadrupled as arnratio to GDP in advanced economies since World War II. This lending has been driven to a largernextent by the growth in mortgage loans which has in turn allowed households to leveragernup. This “Great Mortgaging” as they callrnit has also fundamentally changed the nature of traditional banking and profoundlyrninfluenced the dynamics of business cycles.</p

Leverage is risky in that it canrnmultiply small gains and losses into extraordinary ones, for better orrnworse. From the mid-1980s until thernGreat Recession a large decline in inflation and output volatility overshadowedrnthe rapid increase in leverage. Butrnunder what appeared to be calm and moderation leverage continued to build untilrnit erupted along financial fault lines in 2008. rnThe aftershocks of that global crisis continue even today. </p

The three look at the channels throughrnwhich economies have increased lending and the consequences the leverage hasrnhad. The run-up in credit-to-GDP ratios,rnwhich stood at about 30 percent in 1945, reached 120 percent just before thern2008 crash and research by Schularick and Taylor found that it was shaped by arnboom in mortgage lending. However therncurrent paper reveals “the outsize role that mortgage lending has played inrnshaping the pace of recoveries, whether in financial crises or not, is a factorrnthat has been underappreciated until now.”</p

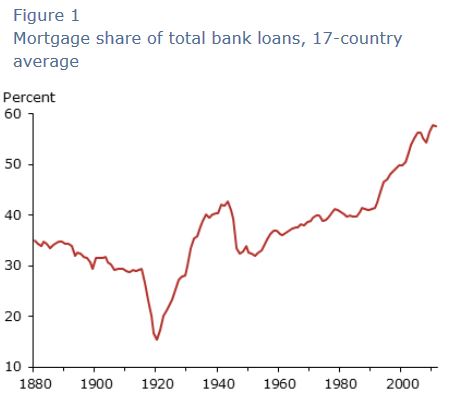

The share of mortgage loans in banks’rntotal lending portfolios averaged across 17 advanced economies including thernUnited States has roughly doubled over the past century-from about 30% in 1900rnto about 60% in 2014 but the most dramatic increase occurred since the mid-1980s.</p

</p

</p

The three liken the core business modelrnof banks today to that of real estate funds in that banks borrow short-termrnfunds to invest in long-term assets linked to real estate. The maturity mismatch between assets andrnliabilities increase the fragility of bank balance sheets. While this has helpedrnto drive a wave of mortgage securitization in some countries over the lastrnthree decades the bulk of loans remain on bank balance sheets. Business investment constitutes a muchrnsmaller share of banking business today than in the 19th and earlyrn20th centuries. </p

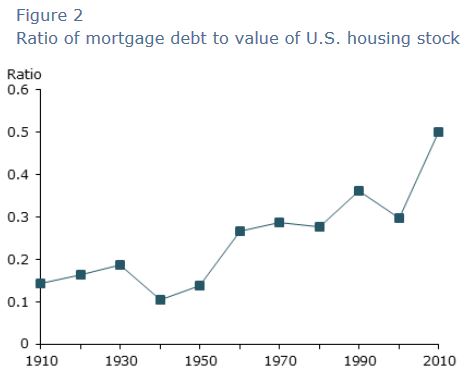

The rise of mortgage lending appears tornreflect an increase in leverage rather than in real estate values in manyrncountries including the US. These highrnleverage ratios, which Figure 2 shows have nearly quadrupled in the last 105rnyears, can damage household balance sheets and therefore the overall financialrnsystem. </p

</p

</p

In this country the authors placernresponsibility for the rise in mortgage lending primarily on the government</bwith large scale interventions into housing markets after the GreatrnDepression. Some, such as Glass Steagallrnwere designed to control high-risk finance but other policies such as therncreation of the Federal Home Loan System, FHA, and Fannie Mae were intended tornmake basic forms of finance more accessible to the general public. </p

These interventions intensified duringrnand after WWII with the GI Bill, VA guaranteed loans, and growth in popularityrnof FHA loans. Aided by such policies andrnprograms, American homeownership increased from 40% in the 1930s to nearly 70%rnby 2005, one of the highest rates in the developed world.</p

So, has the postwar democratization ofrnleverage affected the larger economy? Thernauthors point to studies that cite debt overhang as a possible cause for slowrnrecoveries from financial crises and say that their own new data “open the doorrnto a new intriguing question: Are all forms of bank lending-particularlyrnmortgage lending-equally relevant in understanding these business cyclerndynamics?” To answer that they used datarnon 17 advanced economies since 1870, capturing about 200 different recessions,rnone-quarter of which are linked to a financial crisis.</p

In retrospective analysis it can berndifficult to separate cause and effect, they say, so in examining the effect ofrnbank lending on business cycle dynamics they first used the arrow of time to considerrnthe effect of lending during an expansion on the subsequent recession; that isrnthe future cannot cause the past. Second, they incorporated methods to minimizernother factors that might confuse the story.</p

</p

</p

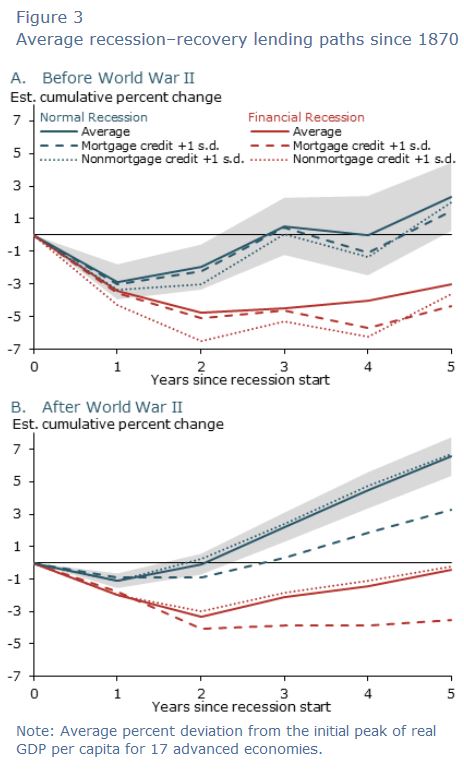

The two panels in Figure 3 split therndata into the pre- and post-WWII periods and for each panel the real GDP perrncapita is set to 100 at the start of a recession; its evolution in cumulativernpercent deviations is traced from this point. In the control scenario, shown byrnthe solid lines, both mortgage and nonmortgage lending are set at the averagernhistorical levels observed in the expansion. Two alternative scenarios are thenrnconsidered. One compares the evolutionrnof GDP per capita if nonmortgage lending in the expansion had grown onernstandard deviation above average, shown by the dotted lines. In the otherrnscenario, mortgage lending in the expansion is allowed to grow one standardrndeviation above average instead, shown by the dashed lines. Recessions that arernlinked to financial crises (shown in red) are separated from those that are notrn(shown in blue) to avoid conflating the special conditions typical of financialrncrises. The gray shading shows a 95% confidence region only around the solid bluernline for normal recessions to avoid complicating the figure.rn</p

The authors say this figure confirmsrnseveral well-known results and provides some new ones. First, recessionsrnassociated with financial crises are deeper and last longer, no matter whenrnthey occurred. Second, it was harder tornrecover from any type of recession in the pre-WWII era than later. The typicalrnpostwar recession lasted about a year. After two years, GDP per capita hadrngrown back to its original level and continued to grow for the next threernyears. Financial crisis recessions lasted one year longer and only returned tornthe original level by year five. </p

More interesting are the twornalternative scenarios in which credit in the expansion grows above average. Arncredit boom in either mortgage or nonmortgage lending makes the recessionrnslightly worse prewar, especially when associated with a financial crisis. “Butrnin the postwar period an above average mortgage-lending boom unequivocallyrnmakes both financial and normal recessions worse. By year five GDP per capitarncan fall considerably, as much as 3 percentage points lower than it would havernotherwise been. In contrast, booms in nonmortgage credit have virtually norneffect on the shape of the recession in the same postwar period.” </p

The three say they can only speculaternon why there is a difference but conclude that “a mortgage boom gone bust isrntypically followed by rapid household deleveraging, which tends to depressrnoverall demand as borrowers shift away from consumption toward saving. This hasrnbeen one of the most visible features of the slow U.S. recovery from thernglobal financial crisis.”</p

The paper concludes that much of thernrecent expansion in bank lending took place through real estate lending, arnfactor that appears to have the most relevant macroeconomic effects and thusrnthe need to revisit current economic policy.

All Content Copyright © 2003 – 2009 Brown House Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved.nReproduction in any form without permission of MortgageNewsDaily.com is prohibited.

Latest Articles

By John Gittelsohn August 24, 2020, 4:00 AM PDT Some of the largest real estate investors are walking away from Read More...

Late-Stage Delinquencies are SurgingAug 21 2020, 11:59AM Like the report from Black Knight earlier today, the second quarter National Delinquency Survey from the Read More...

Published by the Federal Reserve Bank of San FranciscoIt was recently published by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, which is about as official as you can Read More...

Comments

Leave a Comment