Blog

Future Housing Policy Should Consider More than Just FHA's Balance Sheet

The authors of a study just released by the University ofrnNorth Carolina’s Center for Community Capital suggest that the current conditionrnof the Federal Housing Administration’s (FHA) finances is not as important asrnthe public purpose of the agency. </p

In Sustaining andrnExpanding the Market: The Public Purpose of the Federal Housing Administration,rnauthors, Roberto G. Quercia and Kevin A. Park find three essential benefits</bthat FHA has historically provided to the U.S. housing markets; regional andrncountercyclical stabilization, overcoming household wealth constraints, andrnproviding product innovation and standardization. </p

The private sector cannot maintain the mortgage creditrnthrough economic downturns the way the public sector can. FHA and private mortgage insurance (PMI) havernthe same purpose but technical differences that set them apart, especially thernfact that FHA is backed by the full faith and credit of the federal government.rn</p

PMI companies can and do become insolvent, file forrnbankruptcy or are seized by regulators. rnEven those that remain solvent must maintain acceptable levels ofrncapital. While FHA is currently experiencingrnproblems with its capital ratio, it is not illiquid and does not face capitalrnconstraints. The government guaranteerninsures that investors will still value FHA’s insurance.</p

Resiliency is especially important for housing financernbecause of its susceptibility to periods of boom and bust and because of therncircular nature of value. The value of propertyrnwhich serves as collateral for credit is itself dependent on the availabilityrnof credit. Price declines arernparticularly destabilizing because American homeowners are leveraged andrnmortgage debt will deepen housing downturns when homeowners are unable to refinancernto a lower interest rate or move into a new house, lowering marketrnliquidity. A drop in home equityrnincreases the risk of foreclosure and any foreclosure further depresses thernvalue of nearby homes. </p

Conventional riskrnmanagement has difficulty with such systematic phenomena, where probabilitiesrnare not independent but correlated. In contrast, public insurance is extremelyrncapable of diversifying risk across time. </p

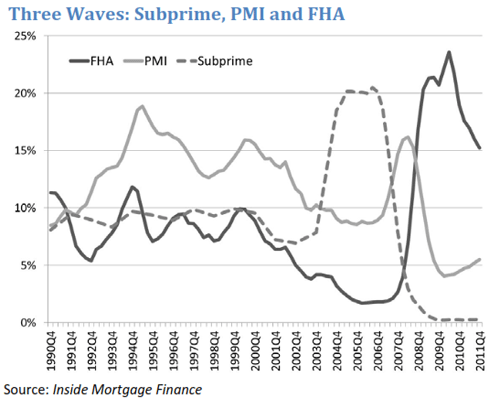

It is easy to see that FHA has a countercyclical role tornthat of PMI. Between 1990 and 2003, PMI accounted for roughly 12.6% of the entirernmortgage market by dollar volume and FHA just 6.7%. Then subprime lenders with high loan-to-valuernratios and subordinate “piggy back” loans stole their market share. As the housing market collapsed, privaternmortgage insurance briefly rallied, but losses constrained its ability to writernnew business. Since the beginning of 2009, private mortgage insurance hasrnaccounted for less than five percent of the market while FHA has accounted forrnalmost 18.6%.</p

</p

</p

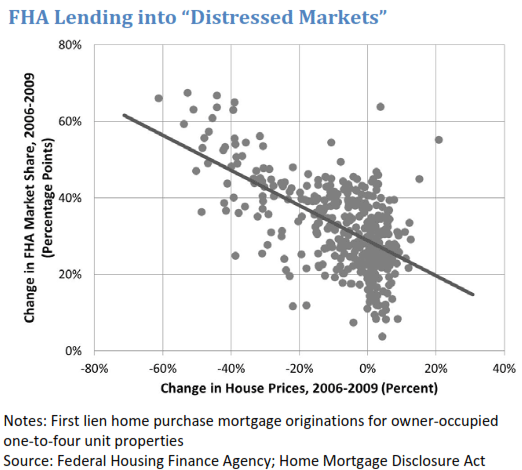

FHA’s is also countercyclical geographically. Private mortgage insurers implementedrn”distressed area” policies, refusing to insure over 90 percent LTV loans inrnsome regions. FHA does not vary itsrninsurance premiums by region, automatically stabilizing distressed areas.</p

</p

</p

Between 2006 and 2009 FHA’s market share of ownerâ€occupiedrnhome purchase mortgages increased most in metropolitan areas that suffered thernlargest decrease in house prices. ThoughrnFHA typically had a very minor role in those markets during the runâ€up,rnthese were the markets most severely cut off from conventional credit when therncrisis hit, and therefore most benefited by FHA’s revival. FHA has always stepped in when and wherernprivate lenders have retreated, preventing a downward spiral of house pricesrnand a reduction in credit availability.</p

A second purpose of FHA has been to serve borrowers andrnneighborhoods poorly served by the private sector. While subprime mortgagernlenders targeted these individuals and regions with disastrous results, FHA hasrnproven capable of supporting sustainable lending to them. </p

Despite higher defaults rates common in loans with high LTVrnratios, FHA has lowered its down payment requirements over the years from 20rnpercent to 5 percent while maintaining a relatively modest rate of claims. Thisrnis particularly important for first time homebuyers who accounted for 75rnpercent of all FHA endorsements in 201. FHArnlending served 41percent of all first time homebuyers. Since the subprime bubble burst FHA hasrnaccounted for 61 percent of purchase mortgages for Hispanic and black borrowersrnand these loans have been more sustainable than products in the conventionalrnmarket.</p

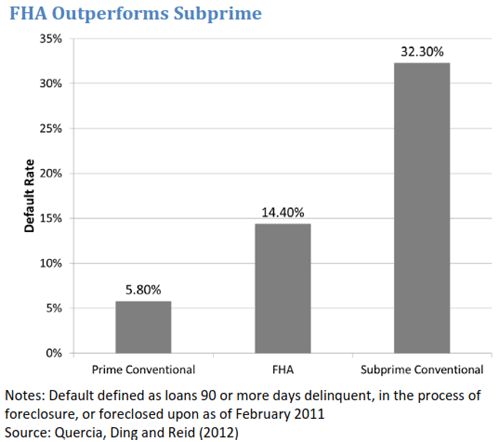

The third essential role of FHA over the years has been torntest and standardize new types of mortgages when the private sector is notrnwilling or able. Many mortgage productsrnnow called “traditional” were pioneered by FHA. rnBefore the Great Depression, most mortgages were shortâ€term,rninterestâ€only loans that had to be continually refinanced. FHA popularized loans that are fullyrnamortizing and with first 20-year and then 30-year terms, which reduced thernrequired monthly payments and increased the acceptable LTV. Fully underwritten 30â€year fixedâ€raternmortgages have accounted for threeâ€fourths of FHA endorsements byrnvolume since FY2000 and FHAâ€insured mortgages have performedrnsignificantly better than conventional subprime mortgages through the GreatrnRecession. </p

</p

</p

The success of FHA led to the rebirth of a private mortgagerninsurance industry in 1957 and revolutionized the secondary mortgage market throughrnGovernment National Mortgage Association (“Ginnie Mae”) guaranties. The experiences of FHAâ€insuredrnmortgages also helped inform the development of credit scoring and automaticrnunderwriting. </p

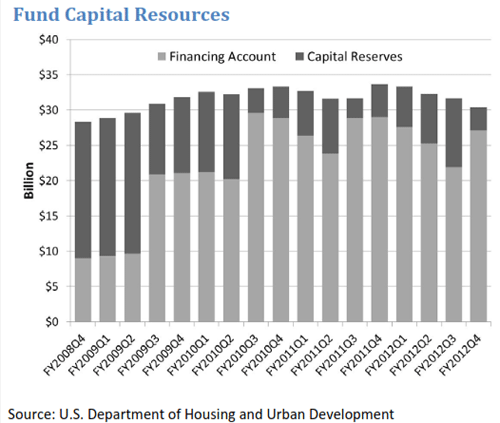

FHA’s Mutual Mortgage Insurance Fund has been selfâ€sustaining</bthrough borrower fees for 80 years. These premiums flow into a financingrnaccount equal to projected costs and a capital reserve account for any remainingrnfunds. The two accounts have over $30 billion in capital resources, which,rngiven the rate of losses of the last four quarters, is enough capital torncontinue paying claims for the next seven to ten years.</p

</p

</p

Unfortunately, not all of FHA’s innovations have provenrnsuccessful. Sellerâ€fundedrndown payment assistance programs artificially inflated sales prices and loanrnamounts and caused high rates of default and substantial Fund losses. HUD attempted to prohibit these loans manyrntimes, but was prevented by legal and political obstacles until 2008. </p

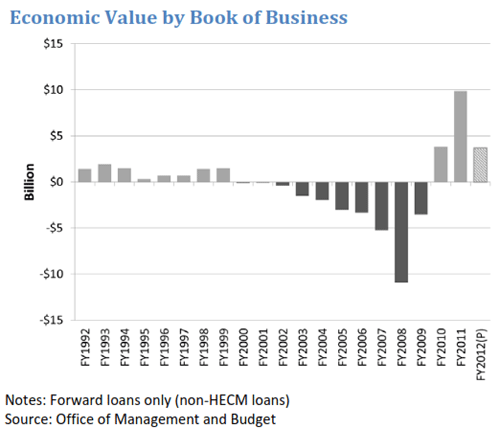

The National Affordable Housing Act mandates that the Fundrnmaintain at least a two percent capital ratio. As recently as FY2007, the Fund had a capitalrnratio of 6.4, but in the last five years, the economic value of “forward” loansrn(which excludes so-called reverse mortgages or HECMs) endorsed by FHA hasrnfallen by almost $35 billion. At the same time, FHA more than tripled its levelrnof insuranceâ€in†force, from $332 billion to overrn$1.1 trillion. The simultaneous decrease in the denominator and the increase inrnthe numerator has caused the capital ratio to fall to under 0.1% in FY2011 andrnultimately to a negative 1.2% in FY2012.</p

As of the latest, FY2012 actuarial review, projected lossesrnon loans (excluding HECMs) are expected to eventually exceed projected revenuesrnand current capital resources by nearly $13.5 billion. HUD’s 2012 report tornCongress notes these losses exceed those projected last year for three reasons:rna lower house price appreciation forecast (â€$10.5 billion); the continuedrndecline in interest rates (â€$8 billion); and a refinement in methodologyrn(â€$10rnbillion).</p

</p

</p

A negative economic value requires FHA to supplement itsrncapital with funds from the U.S. Treasury, an option that was not available inrnthe early 1990s when the fund also had a negative economic value. In that period the Fund was able to grow outrnof its negative position by reforming its premium structure and endorsing newrnbooks of business. The Fund may again grow out of its current predicamentrnwithout exhausting its capital resources. </p

The Fund has $30 billion in capital resources and thernactuarial analysis estimates there is only a five percent chance thesernresources will be exhausted in the next seven years, partially due to its highlyrnprofitable new books of business. Untilrnthe capital resources are exhausted, any Treasury draw would simply be used tornstock the financing account, which is held in Treasury bonds.</p

The authors stress that financial calculations fail tornaccount for FHAs value to the broader economy-its true economic value. The expectation that the MMI Fund shouldrnoperate through a “hundredâ€year flood” like a private companyrnignores its public purpose. Inrnconducting the first independent actuarial study of the fund in 1989 PricernWaterhouse considered a “Great Depression” scenario but argued “the socialrnpurpose of the Fund is such that it should not be expected to withstand such arncalamity” Instead, FHA is intended to use the full faith and credit of thernfederal government to stabilize the housing market even if it means temporaryrntechnical insolvency. </p

By continuing to finance mortgages even as house prices fellrnand unemployment rose, FHA fulfilled its duty to step in when and where thernprivate market fails. Moody’s Analyticsrnestimates that, if FHA had refused to stop insuring new mortgages in October ofrn2010, by the end of 2011 house prices would have fallen another 25%, new andrnexisting home sales would have fallen an additional 40%, and new home constructionrnwould have dropped 60%. This would havernresulting in another two percent contraction of the economy, the loss ofrnanother three million jobs, and an unemployment rate of 12 percent. This would have increased FHA losses as wellrnas that of PMI companies, GSEs, lenders, investors, and American Households. </p

Those who will decide how FHA should be structured goingrnforward should bear in mind how FHA has fulfilled its public purpose over thernpast 80 years and mindful of the agency’s challenges to fulfilling that purpose.rn</p

FHA should be empowered to protect communities from steeringrnand abuses by lenders and given greater flexibility and resources to keep steprnwith the market, particularly in the areas of risk and loss management. Thernagency also faces the onâ€going risk of adverse selectionrnfrom private sector insurers and investors. Policymakers have an extraordinaryrnopportunity to address such fundamental issues as they seek to shape a morerneffective and resilient FHA for the future.</p

It may be tempting to reassess FHA’s role based on itsrncurrent fiscal predicament and while that is concerning further major pricingrnand underwriting changes beyond those already made or underway may not bernnecessary to restore FHA’s financial cushion and improve the value of recentrnyears’ business.</p

Right now an active FHA insurance program is still critical</bfor supporting the fragile housing recovery. FHA's current elevated market share merely indicatesrnthe weakness in the private conventional mortgage market. In fact FHA's market share has alreadyrndecreased substantially from the height of the housing crisis and an overâ€correctionrnmay actually hinder the process of recapitalizing the MMI Fund.</p

The massive portfolios and guarantees of the GSEs arernscheduled to be gradually reduced without any clear sense of what will replacernthem in the secondary market and definitions for Dodd-Frank QualifiedrnResidential Mortgages are not set. Arnstrict standard would limit the conventional lenders’ ability to serve thernentire market so either FHA must be able to do so or else the housing marketrnmust be prepared for a likely drastic reduction in the supply of mortgagerncredit.</p

Even when conventional mortgage lending does return, FHA willrnremain critical to the longâ€term health of the housing marketrnwhich future demand is likely to come from traditionally underserved populations. This is the very type of borrower that FHArnhas served successfully over the decades.</p

The purpose of FHA is to fill in the gaps in thernavailability of mortgage credit and its purpose is likely to become even morernrelevant as a result of the restructuring of housing finance system and of thernlikely demographic changes that will characterize America’s mortgage demand.rnThe actuarial soundness of the Mutual Mortgage Insurance Fund is only anrnindication that FHA fulfills its public purpose efficiently. A full measure ofrnthat efficiency must take into account the whole range of benefits derived fromrnthe fulfillment of its public purpose.

All Content Copyright © 2003 – 2009 Brown House Media, Inc. All Rights Reserved.nReproduction in any form without permission of MortgageNewsDaily.com is prohibited.

Latest Articles

By John Gittelsohn August 24, 2020, 4:00 AM PDT Some of the largest real estate investors are walking away from Read More...

Late-Stage Delinquencies are SurgingAug 21 2020, 11:59AM Like the report from Black Knight earlier today, the second quarter National Delinquency Survey from the Read More...

Published by the Federal Reserve Bank of San FranciscoIt was recently published by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, which is about as official as you can Read More...

Comments

Leave a Comment